Logical Reasoning Essentials

Table of Contents

Blog Content

Introduction: Why Logical Reasoning Separates Thinkers from Followers

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: quantitative aptitude tests mathematical ability, but logical reasoning tests thinking ability. A person can memorize formulas and solve complex calculations. But can they think critically? Can they identify patterns? Can they make deductions from incomplete information?

That’s why companies love logical reasoning questions. In real work, you’ll rarely have perfect information. You’ll receive fragmented data, hidden constraints, and unclear instructions. Your job is to think logically—to draw correct conclusions from limited information. That’s exactly what logical reasoning tests.

Unlike quantitative problems that have definitive right answers, reasoning problems test your problem-solving process. Two candidates might approach the same syllogism problem differently, but both reach the same logical conclusion. The test validates your reasoning framework, not just your math skills.

This module teaches you to think like a logician, not memorize patterns.

🔍 Explore structured learning paths to strengthen analytical decision-making →

Section 1: Syllogisms - The Art of Valid Deduction

Understanding Syllogisms Through Logic, Not Memorization

A syllogism is a logical argument with three components: two premises (statements assumed to be true) and a conclusion (what logically follows from those premises).

Structure:

- Major Premise: A general statement about a group

- Minor Premise: A specific statement about a member of that group

- Conclusion: What logically follows

Classic Example:

- Major Premise: All humans are mortal.

- Minor Premise: Socrates is a human.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

This conclusion is valid because it follows logically from the premises. But here’s where students stumble: they memorize “rules” without understanding the underlying logic.

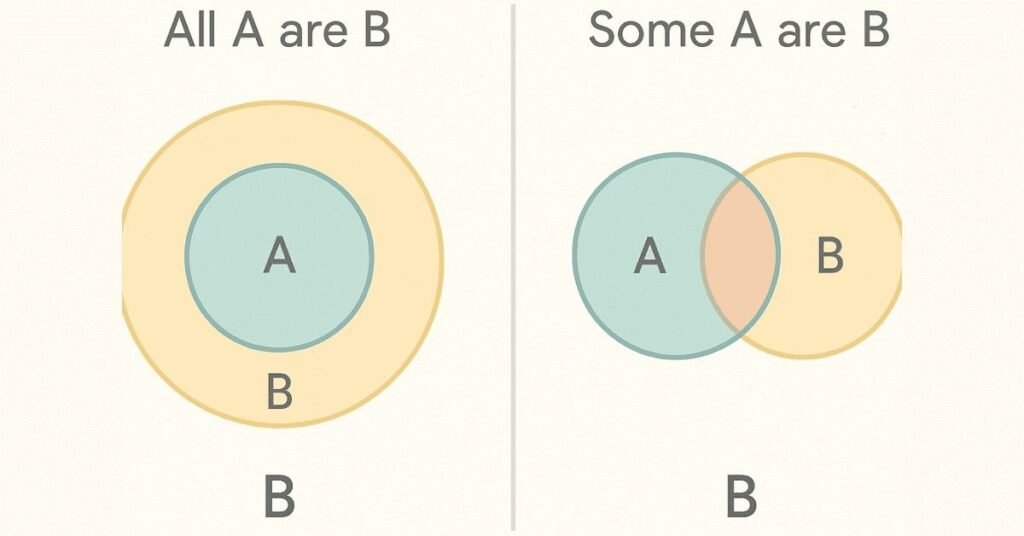

The Real Principle: Set Theory

Remember sets from Module 2? Syllogisms are just set relationships in disguise.

“All humans are mortal” means: The set of humans ⊆ (is a subset of) the set of mortal things.

“Socrates is a human” means: Socrates ∈ (belongs to) the set of humans.

Therefore: Socrates ∈ the set of mortal things.

Visual Representation:

Imagine concentric circles:

- Largest circle: All mortal things

- Medium circle (inside): All humans

- Smallest point (inside): Socrates

If humans are inside mortals, and Socrates is inside humans, then Socrates must be inside mortals. This visual makes the logic obvious.

Quantifiers: The Hidden Complexity

Syllogism complexity comes from quantifiers—words that specify the scope:

- All = Every member (universal, affirmative)

- Some = At least one member (particular, affirmative)

- No = Zero members (universal, negative)

- Some… not = At least one excluded (particular, negative)

Example Problem:

Statement 1: All engineers are mathematicians.

Statement 2: Some mathematicians are teachers.

Conclusion: All engineers are teachers.

Is this valid? Let’s use sets:

- Set E (engineers) ⊆ Set M (mathematicians) ✓

- Set T (teachers) ∩ Set M (mathematicians) = some overlap ✓

But does E ⊆ T? No! The diagram shows engineers inside mathematicians, and teachers also partially inside mathematicians, but engineers might not overlap with teachers at all.

Correct visual:

text

Mathematicians (large circle)

├─ Engineers (inside)

└─ Teachers (overlaps, but separate from engineers)

The conclusion is invalid because it’s possible for all engineers to be mathematicians without being teachers.

Key Rule: “Some” ≠ “All”

This is where most students fail. Just because “some X are Y” and “all Y are Z” doesn’t mean “some X are Z.”

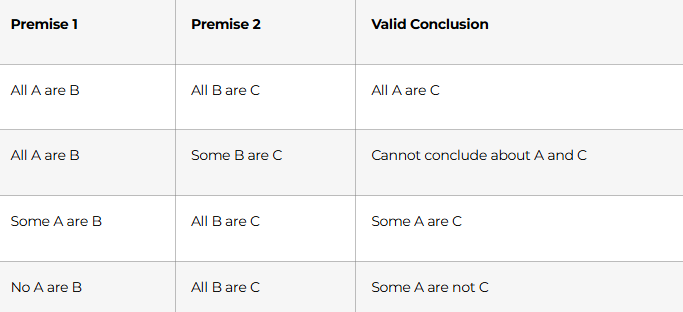

Rule Table for Valid Conclusions:

Problem-Solving Approach for Syllogisms:

- Identify the three terms: Major term (predicate of conclusion), Minor term (subject of conclusion), Middle term (appears in both premises)

- Draw Venn diagrams with three circles representing each set

- Shade or mark regions based on each premise

- Check if the conclusion region is definitely shaded

- Only then is the conclusion valid

Most students skip the diagram step and rely on intuition. That’s why they fail.

📘 Discover more preparation-focused guides designed to build reasoning depth →

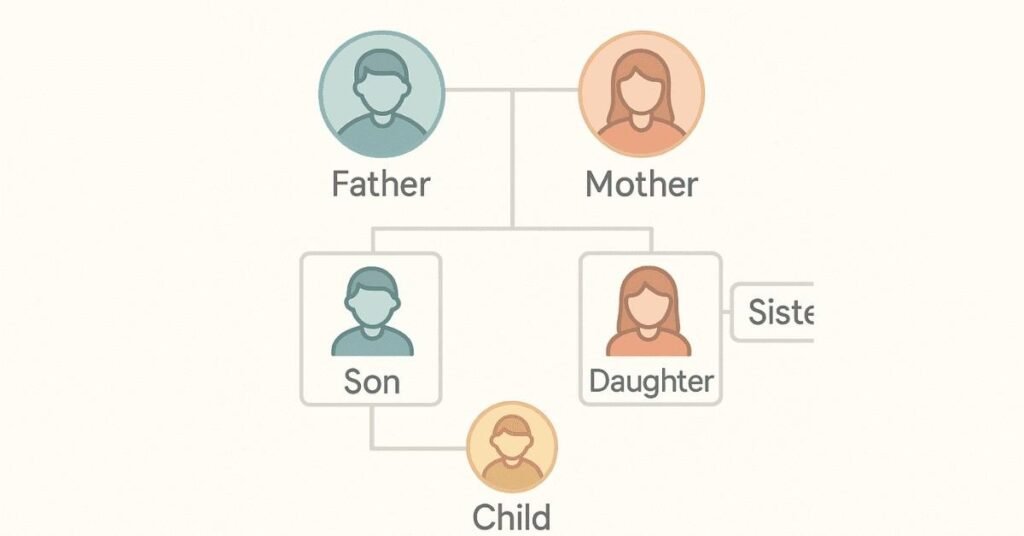

Section 2: Blood Relations and Family Trees - Solving Spatial Puzzles

Why Blood Relations Matter: Pattern Recognition Under Constraints

Blood relation problems test your ability to hold multiple relationships in mind and track them correctly. In business, you’ll manage complex stakeholder relationships, project dependencies, and organizational hierarchies. Blood relations develop exactly this skill.

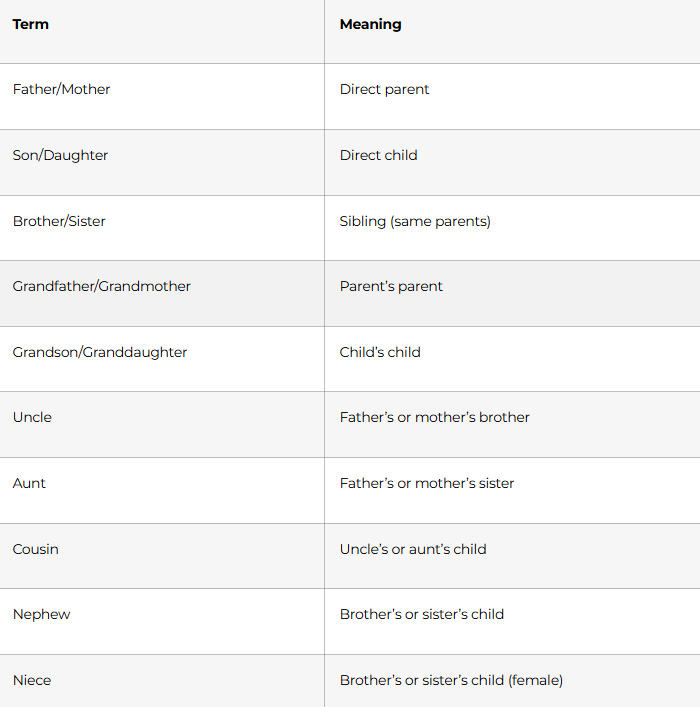

Terminology Clarity:

Day 1-2: Focus on Pacing

- Practice with metronome

- Record and time yourself

- Identify your natural pace

Day 3-4: Focus on Voice Modulation

- Vocal scale exercises

- Practice pitch variation

- Work on volume projection

Day 5-6: Focus on Pronunciation

- Tongue twisters daily

- Mirror practice

- Record and correct unclear sounds

Day 7: Focus on Breathing

- Diaphragmatic breathing exercises

- Strategic pause practice

- Full JAM simulation with all techniques

Repeat this cycle for 3-4 weeks and you’ll see dramatic improvement.

The Reverse Relationship Rule:

Every relationship has a reverse. If X is the father of Y, then Y is the son of X. Many problems test whether you can flip relationships correctly.

Example Problem:

“Pointing to a photograph, Priya says, ‘This woman is the mother of my son’s sister. Who is this woman in the photograph?'”

Solution:

- My son’s sister = my daughter

- The mother of my daughter = me (the speaker, Priya)

So the woman in the photograph is Priya herself. But wait—Priya is saying this while looking at a photograph. So the woman is actually Priya’s sister (because she has a sister who is her son’s sister… wait, let me reconsider).

Actually:

- My son’s sister = This woman’s son’s sister = This woman’s daughter (if this woman is my friend)

- Wait, no. Let me be clearer.

“My son’s sister” = any sibling of my son who is female = my daughter

“The mother of my daughter” = me (Priya)

But Priya is looking at a photograph. So this woman = Priya? No, that doesn’t make sense with a photograph.

Let me reinterpret: “The woman in the photograph is the mother of my son’s sister.”

- My son’s sister could be interpreted as: If I’m a woman, my son’s sister is my other daughter. So the mother of my daughter is… me.

- But it could also mean my son’s sister (from another relationship): then the mother is that woman.

Actually, the simplest reading: I’m a female (Priya). My son has a sister—that’s my daughter. This woman is the mother of my daughter. This woman is me.

So Priya is looking at her own photograph.

Better Example Problem:

“A’s son, B, is married to C. D is A’s grandson. E is C’s sister. How is E related to D?”

Solution:

Let’s map this:

- A has a son B

- B is married to C

- D is A’s grandson (so D is B and C’s child)

- E is C’s sister

Relationships:

- A → B (parent-child)

- B → C (married)

- B and C → D (parents-child)

- C → E (sisters)

Therefore:

- E is C’s sister

- C is D’s mother

- E is D’s mother’s sister = E is D’s aunt

Strategy for Complex Family Problems:

- Draw a family tree with names and connections

- Mark relationships clearly with lines (= for marriage, | for parent-child)

- Trace the path from one person to another

- Identify the relationship at the end

Most mistakes happen because students try to solve mentally without visualization.

Section 3: Coding-Decoding - Breaking Hidden Patterns

Why Coding Matters: Pattern Recognition is Crucial Business Skill

In data science, you decode patterns from raw data. In cybersecurity, you decode encrypted messages. In marketing, you decode customer behavior patterns. Coding-decoding tests your ability to recognize substitution rules and apply them systematically.

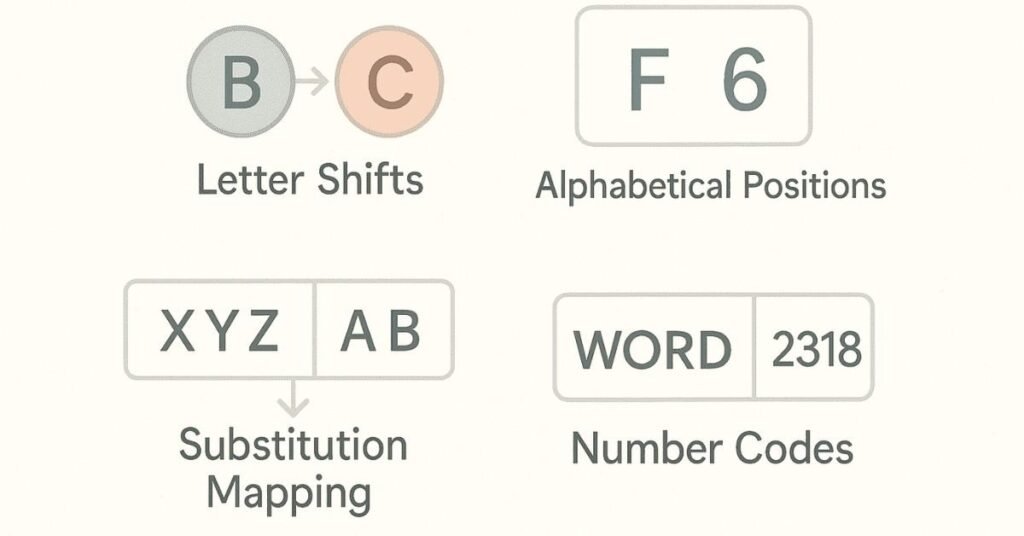

Type 1: Letter Shift Coding

The simplest coding: each letter shifts by a fixed number.

Example: If A = B, B = C, C = D… Z = A (Caesar cipher with shift 1)

Code: “HELLO” = “IFMMP”

Decoding approach:

- Identify the shift pattern by comparing one known pair

- Apply that shift to all letters

Example Problem:

“In a code, FRIEND is written as HUMJSD. How is INDIA written in that code?”

Solution:

Compare FRIEND and HUMJSD:

- F → H (shift of +2)

- R → U (R is 18th letter, U is 21st = shift of +3)

- Wait, different shifts? Let me recount.

F (6th) → H (8th) = +2

R (18th) → U (21st) = +3

I (9th) → M (13th) = +4

E (5th) → J (10th) = +5

N (14th) → S (19th) = +5

D (4th) → D (4th) = 0?

That doesn’t work. Let me recheck:

F(6) H(8) = +2

R(18) U(21) = +3

I(9) M(13) = +4

E(5) J(10) = +5

N(14) S(19) = +5

D(4) D(4) = 0

Hmm, the last letter D→D breaks the pattern. Let me reconsider if this is position-based coding.

Actually, this might be position-based incremental shifting:

- Position 1: shift +2

- Position 2: shift +3

- Position 3: shift +4

- Position 4: shift +5

- Position 5: shift +5

- Position 6: shift +0

For INDIA:

- I (pos 1) + 2 = K

- N (pos 2) + 3 = Q

- D (pos 3) + 4 = H

- I (pos 4) + 5 = N

- A (pos 5) + 5 = F

INDIA = KQHNF

Type 2: Substitution Coding (Letter Mapping)

Each letter consistently maps to a different letter (not positional).

Example: A→D, B→E, C→F… (every letter shifts by 3)

Decoding approach:

- Find multiple letter mappings from examples

- Create a mapping table

- Apply consistently

Type 3: Number Coding

Words are converted to numbers using a rule.

Example Problem:

“In a code, APPLE = 1, BANANA = 2, CHERRY = 3. What is MANGO?”

Solution:

This requires identifying the pattern:

- APPLE = 1 (5 letters)

- BANANA = 2 (6 letters)

- CHERRY = 3 (6 letters)

That doesn’t work. Maybe it’s based on alphabetical order first letters?

- APPLE (A is 1st) = 1

- BANANA (B is 2nd) = 2

- CHERRY (C is 3rd) = 3

- MANGO (M is 13th) = 13

Type 4: Alphanumeric Coding (Mixed)

Letters and numbers are mixed; decode the pattern.

Example Problem:

“If in a code, BOOK is written as 2-15-15-11, how is WORD written?”

Solution:

Each letter converts to its position in the alphabet:

- B = 2

- O = 15

- O = 15

- K = 11

So WORD:

- W = 23

- O = 15

- R = 18

- D = 4

WORD = 23-15-18-4

Type 5: Reverse/Mirror Coding

Words are written backward or letters are mirrored.

Example: HELLO → OLLEH (reverse)

Strategy for All Coding Problems:

- Compare known codes to identify the transformation rule

- Test the rule on multiple examples to confirm

- Apply the rule consistently to the unknown word

- Verify your answer makes sense with the pattern

📂 Access advanced learning resources to improve pattern recognition and logical clarity →

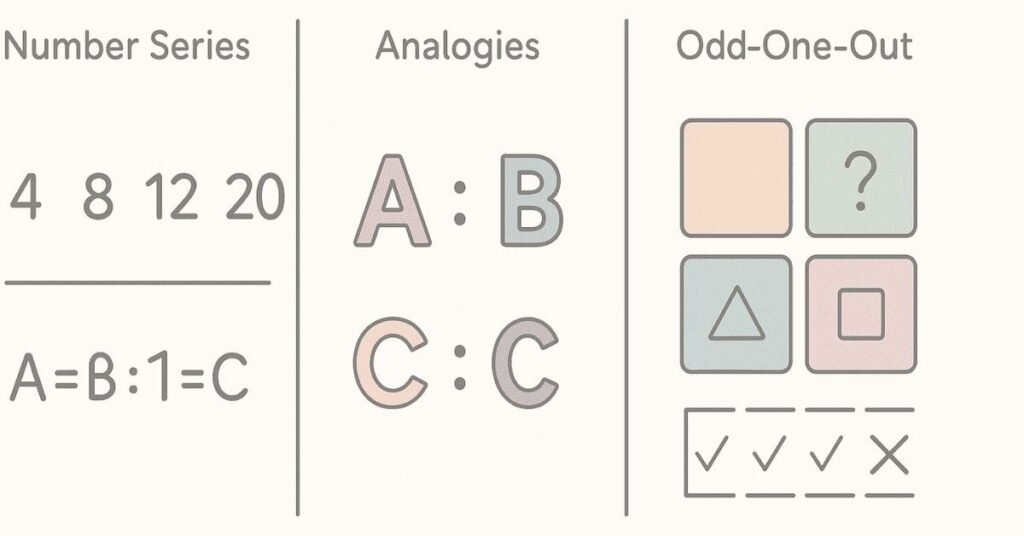

Section 4: Series and Sequences - Pattern Recognition at Scale

Understanding Series Complexity: Single vs. Multiple Patterns

Number and letter series test your ability to recognize patterns. But here’s the key insight: sometimes there are multiple patterns interwoven.

Type 1: Arithmetic Series (Common Difference)

Numbers increase or decrease by a constant amount.

Example: 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, ?

Common difference = 5

Next term = 25 + 5 = 30

Type 2: Geometric Series (Common Ratio)

Numbers multiply or divide by a constant factor.

Example: 2, 6, 18, 54, ?

Common ratio = 3

Next term = 54 × 3 = 162

Type 3: Fibonacci-Like Series

Each term is the sum of the previous two.

Example: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, ?

Next term = 8 + 13 = 21

Type 4: Square/Cube Series

Terms are perfect squares or cubes.

Example: 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, ?

These are 1², 2², 3², 4², 5²

Next term = 6² = 36

Type 5: Series with Multiple Patterns

This is where placement exams get tricky. A series might alternate between two patterns.

Example Problem:

“2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, ?”

Solution:

At first glance, this looks like Fibonacci (each term = sum of previous two):

- 2 + 3 = 5 ✓

- 3 + 5 = 8 ✓

- 5 + 8 = 13 ✓

- 8 + 13 = 21 ✓

Next term = 13 + 21 = 34

Advanced Problem: Series with Decreasing Differences

Example: 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, 16, ?

Differences:

- 2 – 1 = 1

- 4 – 2 = 2

- 7 – 4 = 3

- 11 – 7 = 4

- 16 – 11 = 5

The differences themselves form a series: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5…

Next difference = 6

Next term = 16 + 6 = 22

Type 6: Letter Series – Same Logic, Different Medium

Example: A, C, E, G, I, ?

This is arithmetic with difference = 2 positions in alphabet

Next = K

Example with Multiple Patterns:

“A, Z, B, Y, C, X, D, ?”

Pattern: Alternating letters from start and end of alphabet, moving inward

- Position 1, 26

- Position 2, 25

- Position 3, 24

- Position 4, 23

Next = W = W

Strategy for Series Problems:

- Calculate differences between consecutive terms

- Look for patterns in these differences

- Check if differences form a series (arithmetic, geometric, etc.)

- If stuck, look for multiple interwoven patterns

Verify your answer by checking if it fits the overall pattern

Section 5: Analogies - Understanding Relationships

Why Analogies Matter: Seeing the Bigger Picture

Analogies test whether you understand relationships, not just memorize facts. If A relates to B in a certain way, and we give you C, can you find D such that C relates to D in the same way?

This mirrors real business thinking: “Our product failed in market X; how do we avoid the same failure in market Y?”

Core Principle: Identify the Relationship Type

Type 1: Part-to-Whole Analogy

Part is a component of the whole.

Example: Hand : Body :: Wheel : ?

Answer: Car (hand is part of body; wheel is part of car)

Type 2: Synonym Analogy

Words have similar meanings.

Example: Intelligent : Smart :: Beautiful : ?

Answer: Lovely (intelligent = smart; beautiful = lovely)

Type 3: Antonym Analogy

Words have opposite meanings.

Example: Hot : Cold :: Happy : ?

Answer: Sad (hot and cold are opposites; happy and sad are opposites)

Type 4: Object-Function Analogy

Object is used for a specific function.

Example: Scissors : Cut :: Knife : ?

Answer: Slice (scissors are used to cut; knife is used to slice)

Type 5: Category Analogy

Items belong to the same group.

Example: Tiger : Mammal :: Lizard : ?

Answer: Reptile (tiger is a mammal; lizard is a reptile)

Type 6: Cause-Effect Analogy

One causes the other.

Example: Study : Knowledge :: Exercise : ?

Answer: Fitness (study causes knowledge; exercise causes fitness)

Type 7: Sequence/Order Analogy

Items follow a logical sequence.

Example: Monday : Week :: January : ?

Answer: Year (Monday is part of a week; January is part of a year)

Placement Problem Example:

Problem: Poet : Poem :: Sculptor : ?

Solution:

Identify relationship: Poet creates Poem

Sculptor creates Sculpture

Strategy for Analogy Problems:

- State the relationship clearly: “A is to B as…”

- Test your proposed answer: Does C have the same relationship to D?

- Check for reverse relationships: Sometimes the order matters

- Eliminate options that don’t fit the exact relationship type

Most mistakes happen when students use looser logic like “oh, both are related to art” without identifying the specific relationship.

Section 6: Classification - Grouping and Outliers

Understanding Classification: What Belongs, What Doesn’t

Classification problems ask you to identify which item doesn’t belong in a group, or to find commonalities among diverse items.

Type 1: Find the Odd One Out

Four items are given; three belong together, one doesn’t. Identify which.

Example Problem:

Apple, Banana, Carrot, Date

Analysis:

- Apple = Fruit (sweet, grows on trees)

- Banana = Fruit

- Carrot = Vegetable

- Date = Fruit

Answer: Carrot (it’s the only vegetable; others are fruits)

The Trick: Sometimes the obvious category isn’t the right one.

Example Problem:

Lion, Tiger, Leopard, Cheetah

Obvious answer: All are big cats. None are odd.

But the actual odd one:

- Lion: Lives in groups (pride)

- Tiger: Lives alone

- Leopard: Lives alone

- Cheetah: Lives alone

Answer: Lion (others are solitary; lion is social)

Or:

- Lion: Mane present

- Tiger: Stripes present

- Leopard: Spots present

- Cheetah: No prominent mane/spots; Cheetah is the odd one

The key: multiple classification schemes exist. Placement tests often use non-obvious schemes to test deeper thinking.

Type 2: Find the Relationship Among Three, Complete the Fourth

“A, B, C are related. D is related to which of these?” (or complete the set)

Example:

Football : Basketball : Volleyball : ?

Common relationship: Ball sports

Answer options: Tennis (also ball sport), Cricket (also ball sport), Chess (not a ball sport)

All three options are ball sports, but the question might ask which is most similar (team sports, outdoor sports, etc.)

Strategy for Classification:

- Identify surface characteristics: Color, shape, category, size

- Look for deeper patterns: Function, origin, properties, behavior

- List multiple possible relationships before choosing an answer

Verify the odd one out by testing it against the relationship you identified

🧭 Continue your learning journey with expert-written content for consistent improvement →