Advanced Quantitative Concepts

Table of Contents

Blog Content

Introduction: Why Advanced Concepts Separate Good Candidates from Excellent Ones

By now, you’ve mastered the fundamentals—percentages, P&L, time-speed-distance. These topics are your baseline. But here’s what distinguishes candidates who clear placements versus those who don’t: the ability to handle complex, multi-step problems under time pressure.

Advanced quantitative concepts test this ability ruthlessly. A permutation-combination question might require you to understand both principles simultaneously. A probability problem might demand you recognize when to use set theory. These aren’t isolated skills—they’re interconnected problem-solving muscles.

Companies like Goldman Sachs, Google, and Amazon use these advanced questions specifically because they mirror real business scenarios. Whether analyzing customer segments (set theory), calculating project outcomes (probability), or optimizing arrangements (permutations), these concepts directly apply to work.

The beautiful part? Advanced doesn’t mean difficult. It means organized thinking. Once you understand the fundamental principle, the problems become patterns you recognize and solve systematically.

Section 1: Permutations - When Order Matters

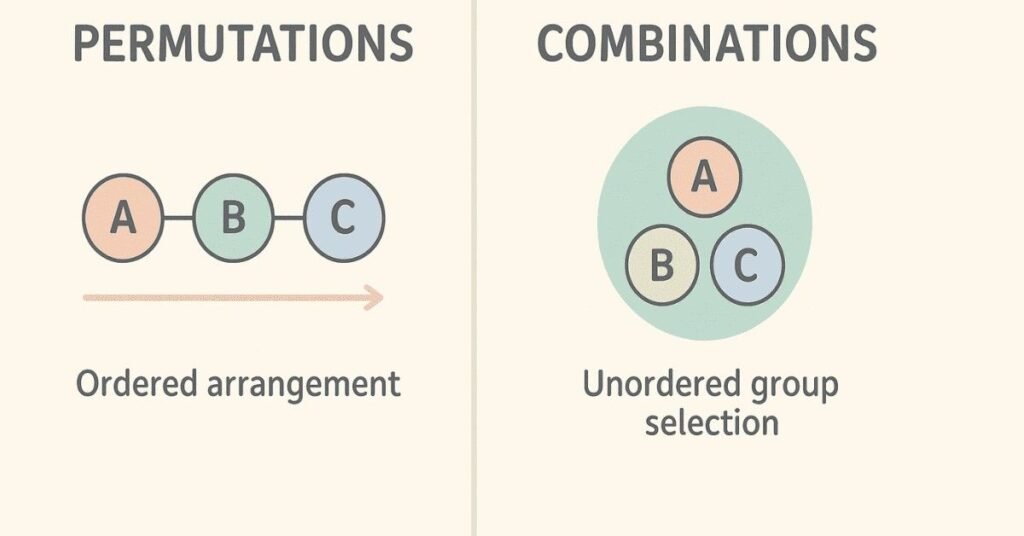

Understanding the Core Difference: Order vs. Selection

Here’s where most students get confused. They hear “permutation” and “combination” and see them as similar concepts with different formulas. Wrong approach.

Permutation answers: “In how many ordered arrangements can I arrange these items?”

Combination answers: “In how many ways can I select these items (where order doesn’t matter)?”

Think of a real scenario: You’re hosting a dinner party.

- If you’re arranging 4 friends in a row (who sits where matters) = Permutation

- If you’re selecting 4 friends from 10 to invite (doesn’t matter who you pick first) = Combination

Basic Permutation: Arranging All Items

If you have 5 books and want to arrange them on a shelf, how many ways can you do it?

- First position: 5 choices

- Second position: 4 remaining choices

- Third position: 3 remaining choices

- Fourth position: 2 remaining choices

- Fifth position: 1 remaining choice

Total arrangements = 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1 = 5! = 120 ways

This is called factorial notation. The factorial of n (written as n!) means:

n!=n×(n−1)×(n−2)×…×2×1n! = n \times (n-1) \times (n-2) \times … \times 2 \times 1n!=n×(n−1)×(n−2)×…×2×1

Core Permutation Formula: nPr (n Permute r)

What if you have 10 books but only 4 shelf spaces? Now order matters, but you’re not using all items.

nPr=n!(n−r)!nPr = \frac{n!}{(n-r)!}nPr=(n−r)!n!

Where:

- n = total items

- r = items to arrange

Example: Arrange 4 books from 10 books in a row.

10P4=10!(10−4)!=10!6!=10×9×8×7×6!6!=10×9×8×7=5,04010P4 = \frac{10!}{(10-4)!} = \frac{10!}{6!} = \frac{10 \times 9 \times 8 \times 7 \times 6!}{6!} = 10 \times 9 \times 8 \times 7 = 5,04010P4=(10−4)!10!=6!10!=6!10×9×8×7×6!=10×9×8×7=5,040

Why This Formula Works: You multiply n choices for the first position, (n-1) for the second, (n-2) for the third, and so on until you’ve filled r positions. The formula cancels out the remaining unused items via factorial division.

Real Placement Problem: President, VP, Secretary

“In a group of 8 candidates, how many ways can you select a President, Vice President, and Secretary?”

This is a permutation problem because:

- Each position is unique (order matters)

- You’re selecting 3 from 8

8P3=8!5!=8×7×6=336 ways8P3 = \frac{8!}{5!} = 8 \times 7 \times 6 = 336 \text{ ways}8P3=5!8!=8×7×6=336 ways

Advanced Concept: Permutations with Restrictions

“From 8 candidates, how many ways to select President, VP, and Secretary if Candidate A must be President?”

Now order still matters, but we have a constraint.

Solution:

- President = Candidate A (fixed, 1 choice)

- VP = Choose from remaining 7

- Secretary = Choose from remaining 6

Total = 1 × 7 × 6 = 42 ways

Advanced Concept: Permutations with Identical Objects

What if you need to arrange letters in the word “BANANA”?

B-A-N-A-N-A has 6 letters, but 3 are A’s and 2 are N’s.

If all letters were different: 6! = 720 arrangements

But since identical letters create duplicate arrangements:

Arrangements=6!3!×2!=7206×2=72012=60\text{Arrangements} = \frac{6!}{3! \times 2!} = \frac{720}{6 \times 2} = \frac{720}{12} = 60Arrangements=3!×2!6!=6×2720=12720=60

Formula for Identical Objects:

Permutations=n!n1!×n2!×…×nk!\text{Permutations} = \frac{n!}{n_1! \times n_2! \times … \times n_k!}Permutations=n1!×n2!×…×nk!n!

Where n₁, n₂, etc. are frequencies of identical items.

Enhance Your Quantitative Skills — Explore Structured Learning Paths ➜ Build mastery with well-designed modules across all technical domains

Section 2: Combinations - When Order Doesn't Matter

Understanding Combinations Through Real Business

Imagine you’re building a 3-person committee from 8 team members. Whether you pick Raj, Priya, and Amit versus Amit, Priya, and Raj doesn’t matter—it’s the same committee.

This is combination. Selection without regard to arrangement order.

Core Combination Formula: nCr (n Choose r)

nCr=n!r!×(n−r)!nCr = \frac{n!}{r! \times (n-r)!}nCr=r!×(n−r)!n!

Example: Select a 3-person committee from 8 people.

8C3=8!3!×5!=8×7×63×2×1=3366=56 ways8C3 = \frac{8!}{3! \times 5!} = \frac{8 \times 7 \times 6}{3 \times 2 \times 1} = \frac{336}{6} = 56 \text{ ways}8C3=3!×5!8!=3×2×18×7×6=6336=56 ways

Why This Formula Works: We start with 8P3 = 336 (ordered arrangements of 3 from 8). But since order doesn’t matter in combinations, we divide by 3! (the ways to arrange 3 selected people among themselves) to eliminate duplicate combinations.

Quick Insight: Relationship Between Permutations and Combinations

nPr=nCr×r!nPr = nCr \times r!nPr=nCr×r!

This makes intuitive sense: every combination can be arranged r! ways.

Placement Problem Example:

“From 10 software developers, select 4 for Project A. How many ways?”

Since the 4 selected developers will all work on the same project (order irrelevant):

10C4=10!4!×6!=10×9×8×74×3×2×1=5,04024=210 ways10C4 = \frac{10!}{4! \times 6!} = \frac{10 \times 9 \times 8 \times 7}{4 \times 3 \times 2 \times 1} = \frac{5,040}{24} = 210 \text{ ways}10C4=4!×6!10!=4×3×2×110×9×8×7=245,040=210 ways

Advanced Concept: Combinations with Restrictions

“From 10 developers (6 frontend, 4 backend), select 4 developers with at least 2 backend developers.”

This requires breaking the problem into cases:

Case 1: Exactly 2 backend developers

- Select 2 from 4 backend: 4C2 = 6

- Select 2 from 6 frontend: 6C2 = 15

- Total for Case 1: 6 × 15 = 90

Case 2: Exactly 3 backend developers

- Select 3 from 4 backend: 4C3 = 4

- Select 1 from 6 frontend: 6C1 = 6

- Total for Case 2: 4 × 6 = 24

Case 3: Exactly 4 backend developers

- Select 4 from 4 backend: 4C4 = 1

- Select 0 from frontend: 6C0 = 1

- Total for Case 3: 1 × 1 = 1

Total Ways = 90 + 24 + 1 = 115 ways

Get Access to More Technical Guides ➜ Continue learning with curated resources, insights, and expert-written tutorials

Section 3: Probability - Predicting Uncertain Outcomes

Why Probability Matters in Modern Business

Every business decision involves uncertainty. Marketing teams ask: “What’s the probability this customer will convert?” Product teams ask: “What’s the probability our feature will succeed?” Operations teams ask: “What’s the probability we’ll meet our target?”

Probability quantifies uncertainty. Companies test your probability thinking because they need employees who can make data-driven decisions despite incomplete information.

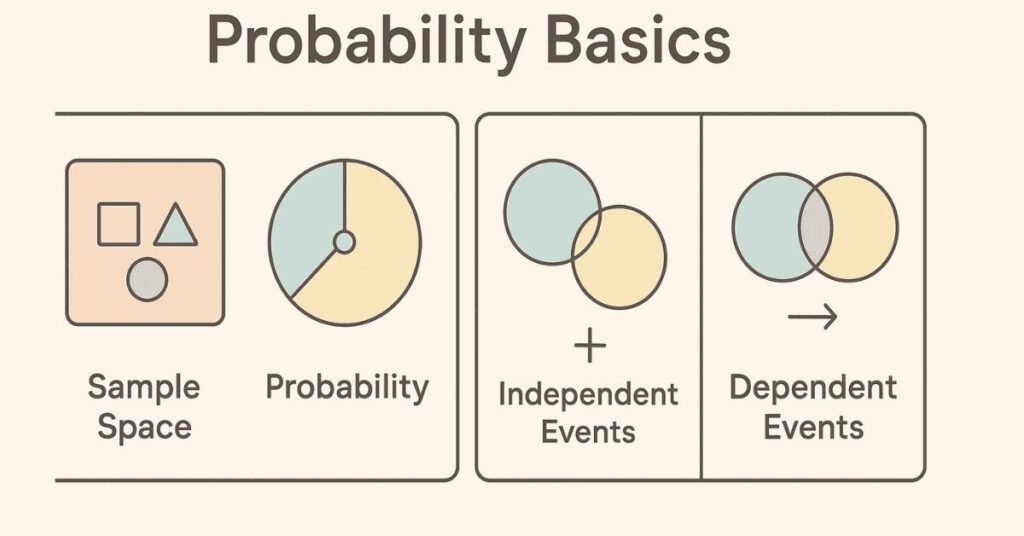

Fundamental Concept: Sample Space and Events

Sample Space (S) = All possible outcomes

Event (E) = Specific outcomes we’re interested in

Probability Formula:

P(E)=Number of favorable outcomesTotal number of possible outcomes=n(E)n(S)P(E) = \frac{\text{Number of favorable outcomes}}{\text{Total number of possible outcomes}} = \frac{n(E)}{n(S)}P(E)=Total number of possible outcomesNumber of favorable outcomes=n(S)n(E)

Simple Example: Rolling a Die

Sample Space = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

Total possible outcomes = 6

Event: Getting an even number = {2, 4, 6}

Favorable outcomes = 3

P(even)=36=12=0.5 or 50%P(\text{even}) = \frac{3}{6} = \frac{1}{2} = 0.5 \text{ or } 50\%P(even)=63=21=0.5 or 50%

Understanding Probability Range

- P(E) = 0 → Event is impossible

- 0 < P(E) < 1 → Event is possible

- P(E) = 1 → Event is certain

Critical Concept: Independent vs. Dependent Events

Two events are independent if one happening doesn’t affect the other.

Two events are dependent if one happening changes the probability of the other.

Independent Events Example:

- Flipping a coin twice

- Rolling two dice

- Drawing a card, replacing it, then drawing again

For independent events:

P(A and B)=P(A)×P(B)P(A \text{ and } B) = P(A) \times P(B)P(A and B)=P(A)×P(B)

Example: What’s the probability of getting heads twice in a row?

P(HH)=P(first H)×P(second H)=12×12=14=25%P(\text{HH}) = P(\text{first H}) \times P(\text{second H}) = \frac{1}{2} \times \frac{1}{2} = \frac{1}{4} = 25\%P(HH)=P(first H)×P(second H)=21×21=41=25%

Dependent Events Example:

- Drawing 2 cards from a deck without replacement

- Selecting 2 people from a group without repetition

For dependent events:

P(A and B)=P(A)×P(B∣A)P(A \text{ and } B) = P(A) \times P(B|A)P(A and B)=P(A)×P(B∣A)

Where P(B|A) means “probability of B given A already happened”

Example: What’s the probability of drawing 2 aces from a standard deck (without replacement)?

- Total cards = 52, Total aces = 4

- P(first ace) = 4/52

- After drawing one ace: 51 cards left, 3 aces left

- P(second ace | first ace drawn) = 3/51

P(both aces)=452×351=122,652=1221≈0.45%P(\text{both aces}) = \frac{4}{52} \times \frac{3}{51} = \frac{12}{2,652} = \frac{1}{221} \approx 0.45\%P(both aces)=524×513=2,65212=2211≈0.45%

Key Difference: Notice how the second probability changed (from 4/52 to 3/51) because we removed a card. That’s dependency.

Important Rule: Addition Rule for Mutually Exclusive Events

Two events are mutually exclusive if they can’t happen simultaneously (e.g., rolling a 3 and a 5 on one die).

For mutually exclusive events:

P(A or B)=P(A)+P(B)P(A \text{ or } B) = P(A) + P(B)P(A or B)=P(A)+P(B)

Example: Probability of rolling either 3 or 5 on one die.

P(3 or 5)=16+16=26=13P(3 \text{ or } 5) = \frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{6} = \frac{2}{6} = \frac{1}{3}P(3 or 5)=61+61=62=31

Important Rule: Addition Rule for Non-Exclusive Events

Sometimes events can happen together (e.g., selecting a card that’s both red AND a face card).

For non-exclusive events:

P(A or B)=P(A)+P(B)−P(A and B)P(A \text{ or } B) = P(A) + P(B) – P(A \text{ and } B)P(A or B)=P(A)+P(B)−P(A and B)

Example: From a deck, what’s the probability of drawing a red card OR a face card?

- P(red) = 26/52

- P(face card) = 12/52

- P(red AND face card) = 6/52 (red face cards)

P(red or face)=2652+1252−652=3252=813P(\text{red or face}) = \frac{26}{52} + \frac{12}{52} – \frac{6}{52} = \frac{32}{52} = \frac{8}{13}P(red or face)=5226+5212−526=5232=138

Complement Rule: “At Least One” Problems

Many placement problems ask: “What’s the probability of at least one successful outcome?”

Instead of calculating directly (which involves many cases), use the complement:

P(at least one)=1−P(none)P(\text{at least one}) = 1 – P(\text{none})P(at least one)=1−P(none)

Example: If 3 people each have a 60% chance of passing an exam, what’s the probability that at least one passes?

- P(one person passes) = 0.6

- P(one person fails) = 0.4

- P(all three fail) = 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.4 = 0.064

P(at least one passes)=1−0.064=0.936=93.6%P(\text{at least one passes}) = 1 – 0.064 = 0.936 = 93.6\%P(at least one passes)=1−0.064=0.936=93.6%

This is much faster than calculating P(exactly 1 passes) + P(exactly 2 pass) + P(all 3 pass).

Placement Test Problem: Combination + Probability

“A committee of 3 is selected from 6 men and 4 women. What’s the probability that the committee has at least 1 woman?”

Total ways to select 3 from 10: 10C3 = 120

Method 1: Direct Calculation

- 1 woman, 2 men: 4C1 × 6C2 = 4 × 15 = 60

- 2 women, 1 man: 4C2 × 6C1 = 6 × 6 = 36

- 3 women, 0 men: 4C3 × 6C0 = 4 × 1 = 4

- Total favorable = 60 + 36 + 4 = 100

P(at least 1 woman)=100120=56P(\text{at least 1 woman}) = \frac{100}{120} = \frac{5}{6}P(at least 1 woman)=120100=65

Method 2: Complement (Faster)

- No women (all 3 men): 6C3 = 20

- P(all men) = 20/120 = 1/6

P(at least 1 woman)=1−16=56P(\text{at least 1 woman}) = 1 – \frac{1}{6} = \frac{5}{6}P(at least 1 woman)=1−61=65

Notice how the complement method is cleaner and faster.

Section 4: Set Theory and Venn Diagrams - Visual Problem Solving

Why Set Theory Matters: Real Business Segmentation

Companies constantly segment their customer base: “How many customers bought Product A OR Product B?” “How many bought both?” “How many bought neither?” These are set theory questions.

Understanding sets helps you visualize complex problems, especially when multiple conditions overlap.

Set Fundamentals

A set is a collection of distinct items. We use:

- Capital letters for sets: A, B, C

- Curly braces for listing: A = {1, 2, 3, 4}

- Symbols for relationships:

- ∪ (union) = “or” – elements in A or B or both

- ∩ (intersection) = “and” – elements in both A and B

- A’ = complement – elements NOT in A

- ∪ (union) = “or” – elements in A or B or both

Set Theory Formula: The Union Rule

n(A∪B)=n(A)+n(B)−n(A∩B)n(A \cup B) = n(A) + n(B) – n(A \cap B)n(A∪B)=n(A)+n(B)−n(A∩B)

This formula answers: “How many elements are in A or B (or both)?”

Why subtract the intersection? Because when you add n(A) + n(B), elements in both A and B get counted twice. Subtracting once fixes this.

Real Business Example:

A company surveyed 100 employees. 60 use Gmail, 40 use Outlook, and 15 use both.

How many use at least one email service?

n(Gmail∪Outlook)=60+40−15=85n(\text{Gmail} \cup \text{Outlook}) = 60 + 40 – 15 = 85n(Gmail∪Outlook)=60+40−15=85

85 employees use at least one email service.

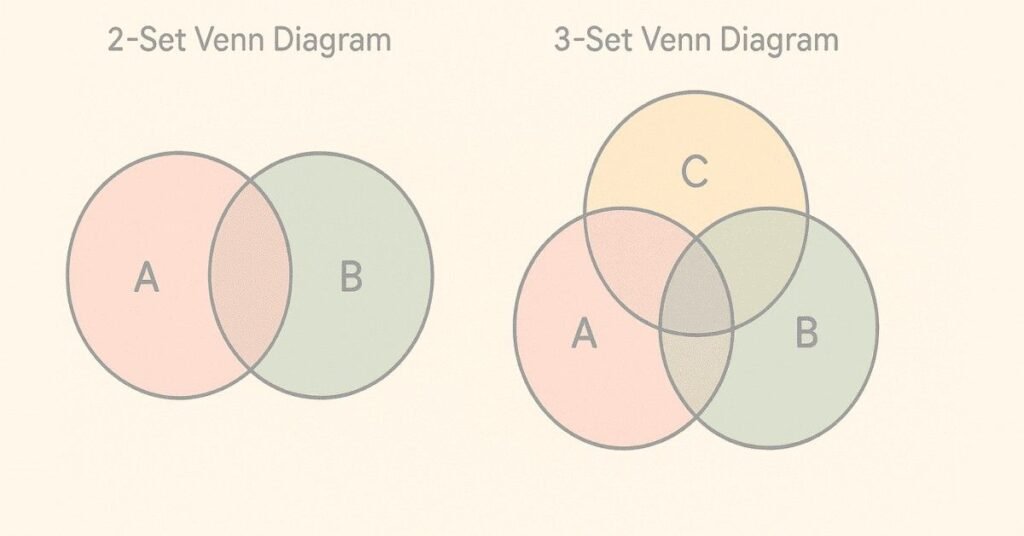

Visual Representation: Venn Diagrams

For two sets A and B, the Venn diagram has three regions:

- Only A (in A but not B)

- Both A and B (intersection)

- Only B (in B but not A)

Formula Breakdown:

- Only A = n(A) – n(A ∩ B) = 60 – 15 = 45

- Both = n(A ∩ B) = 15

- Only B = n(B) – n(A ∩ B) = 40 – 15 = 25

- Total using at least one = 45 + 15 + 25 = 85 ✓

Three-Set Problems (More Complex)

When dealing with three sets A, B, and C:

n(A∪B∪C)=n(A)+n(B)+n(C)−n(A∩B)−n(B∩C)−n(A∩C)+n(A∩B∩C)n(A \cup B \cup C) = n(A) + n(B) + n(C) – n(A \cap B) – n(B \cap C) – n(A \cap C) + n(A \cap B \cap C)n(A∪B∪C)=n(A)+n(B)+n(C)−n(A∩B)−n(B∩C)−n(A∩C)+n(A∩B∩C)

This looks complex, but follow the logic:

- Add all three sets

- Subtract pairwise intersections (to remove double counting)

- Add back the three-way intersection (because subtracting it removed elements that belong to all three)

Example: 100 students surveyed

- Study Math: 50

- Study Physics: 40

- Study Chemistry: 30

- Study Math and Physics: 15

- Study Physics and Chemistry: 10

- Study Math and Chemistry: 8

- Study all three: 3

How many study at least one subject?

n(M∪P∪C)=50+40+30−15−10−8+3=90n(M \cup P \cup C) = 50 + 40 + 30 – 15 – 10 – 8 + 3 = 90n(M∪P∪C)=50+40+30−15−10−8+3=90

90 students study at least one subject.

Section 5: Arithmetic Progressions - Understanding Linear Patterns

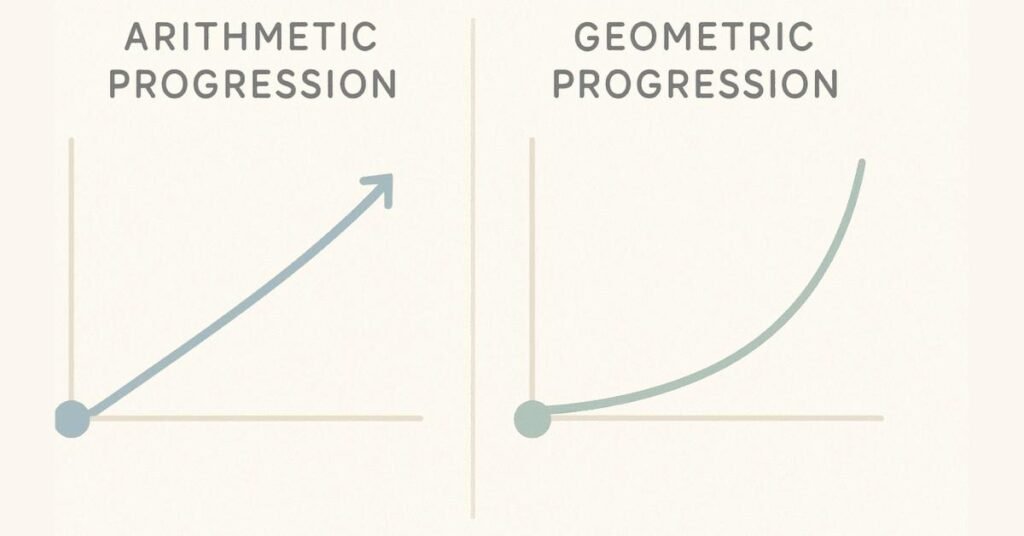

Why Progressions Matter: Predictable Growth

Business scenarios often show predictable patterns. Salary increases at fixed rates, inventory depletion follows patterns, loan EMI calculations use sequences. Understanding progressions helps you predict these outcomes mathematically.

Definition and Terminology

An Arithmetic Progression (AP) is a sequence where the difference between consecutive terms is constant.

Example: 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, … (common difference = 3)

Terminology:

- First term (a) = 2

- Common difference (d) = 3

- nth term (Tₙ) = any term in the sequence

Formula for nth Term of AP:

Tn=a+(n−1)dT_n = a + (n-1)dTn=a+(n−1)d

Example: Find the 10th term of AP: 3, 7, 11, …

- a = 3

- d = 7 – 3 = 4

- n = 10

T10=3+(10−1)×4=3+36=39T_{10} = 3 + (10-1) \times 4 = 3 + 36 = 39T10=3+(10−1)×4=3+36=39

Formula for Sum of n Terms of AP:

Sn=n2[2a+(n−1)d]S_n = \frac{n}{2}[2a + (n-1)d]Sn=2n[2a+(n−1)d]

Alternative form:

Sn=n2[a+l]S_n = \frac{n}{2}[a + l]Sn=2n[a+l]

Where l = last term = a + (n-1)d

Example: Find the sum of first 10 terms of AP: 3, 7, 11, …

Using first formula:

S10=102[2(3)+(10−1)(4)]=5[6+36]=5×42=210S_{10} = \frac{10}{2}[2(3) + (10-1)(4)] = 5[6 + 36] = 5 \times 42 = 210S10=210[2(3)+(10−1)(4)]=5[6+36]=5×42=210

Or using second formula (where l = 39):

S10=102[3+39]=5×42=210S_{10} = \frac{10}{2}[3 + 39] = 5 \times 42 = 210S10=210[3+39]=5×42=210

Real-World Example: Salary Progression

You start with ₹30,000 monthly salary, with annual increments of ₹2,000. Calculate your salary after 5 years (at the start of year 6).

This is an AP: 30,000, 32,000, 34,000, 36,000, 38,000, 40,000

After 5 years: a = 30,000, d = 2,000, n = 6 (including starting year)

T6=30,000+(6−1)×2,000=30,000+10,000=₹40,000T_6 = 30,000 + (6-1) \times 2,000 = 30,000 + 10,000 = ₹40,000T6=30,000+(6−1)×2,000=30,000+10,000=₹40,000

Placement Problem: Sum Application

“An employee saves money following an AP pattern: ₹100 in month 1, ₹150 in month 2, ₹200 in month 3, and so on. How much total does she save in 12 months?”

- a = 100, d = 50, n = 12

S12=122[2(100)+(12−1)(50)]=6[200+550]=6×750=₹4,500S_{12} = \frac{12}{2}[2(100) + (12-1)(50)] = 6[200 + 550] = 6 \times 750 = ₹4,500S12=212[2(100)+(12−1)(50)]=6[200+550]=6×750=₹4,500

Section 6: Geometric Progressions - Understanding Exponential Growth

Why Geometric Progressions Matter: Exponential Real-World Growth

Unlike AP’s steady growth, many real phenomena show exponential growth: bacterial multiplication, compound interest (which you learned earlier is actually GP!), viral spread, population growth. Companies test GP because it models real business scenarios like customer base expansion or technology adoption.

Definition and Terminology

A Geometric Progression (GP) is a sequence where the ratio between consecutive terms is constant.

Example: 2, 6, 18, 54, 162, … (common ratio = 3)

Terminology:

- First term (a) = 2

- Common ratio (r) = 6/2 = 3

- nth term (Tₙ) = any term in the sequence

Formula for nth Term of GP:

Tn=a×rn−1T_n = a \times r^{n-1}Tn=a×rn−1

Example: Find the 5th term of GP: 2, 6, 18, …

- a = 2

- r = 3

- n = 5

T5=2×35−1=2×34=2×81=162T_5 = 2 \times 3^{5-1} = 2 \times 3^4 = 2 \times 81 = 162T5=2×35−1=2×34=2×81=162

Formula for Sum of n Terms of GP:

When r ≠ 1:

Sn=a×rn−1r−1S_n = a \times \frac{r^n – 1}{r – 1}Sn=a×r−1rn−1

Example: Find sum of first 5 terms: 2, 6, 18, …

S5=2×35−13−1=2×243−12=2×2422=242S_5 = 2 \times \frac{3^5 – 1}{3 – 1} = 2 \times \frac{243 – 1}{2} = 2 \times \frac{242}{2} = 242S5=2×3−135−1=2×2243−1=2×2242=242

Verification: 2 + 6 + 18 + 54 + 162 = 242 ✓

Connection to Compound Interest

Remember compound interest formula?

A=P(1+r/100)nA = P(1 + r/100)^nA=P(1+r/100)n

This is actually a GP! The amount each year forms a geometric sequence:

- Year 1: P(1 + r/100)¹

- Year 2: P(1 + r/100)²

- Year 3: P(1 + r/100)³

With first term a = P and common ratio r = (1 + r/100)

Real Example: ₹1,000 invested at 10% compound interest for 4 years forms a GP:

- Year 1: 1,000 × 1.1 = ₹1,100

- Year 2: 1,000 × 1.1² = ₹1,210

- Year 3: 1,000 × 1.1³ = ₹1,331

- Year 4: 1,000 × 1.1⁴ = ₹1,464.10

Common ratio = 1.1

Advance Your Preparation With Industry-Ready Learning Resources ➜ Deepen your quantitative reasoning with comprehensive course materials & practice-driven content.

Section 7: Algebra and Equations - Solving Multi-Variable Problems

Why Algebra Matters: Systematic Problem Solving

Many placement problems can’t be solved with mental math or simple formulas. You need to set up equations to represent relationships, then solve systematically. This algebraic thinking mirrors how engineers, data scientists, and business analysts work.

Setting Up Equations from Word Problems

The key skill is translating English statements into mathematical equations.

Translation Guide:

English | Math |

“A number” | x |

“Sum of two numbers” | x + y |

“Difference” | x – y |

“Product” | x × y or xy |

“Quotient” | x/y or x ÷ y |

“Twice a number” | 2x |

“Exceeds by” | x = y + 5 (if x exceeds y by 5) |

“Ratio” | x:y or x/y |

Example Problem: “The sum of two numbers is 25. Their difference is 5. Find the numbers.”

Let the two numbers be x and y.

- Equation 1: x + y = 25

- Equation 2: x – y = 5

Adding both equations:

2x = 30 → x = 15

Substituting in Equation 1:

15 + y = 25 → y = 10

Quadratic Equations – When Linear Isn’t Enough

Some placement problems involve relationships that aren’t linear. These create quadratic equations: ax² + bx + c = 0

Formula to Solve:

x=−b±b2−4ac2ax = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 – 4ac}}{2a}x=2a−b±b2−4ac

Example Problem: “The area of a rectangular garden is 120 m². Its length is 7 m more than its width. Find the dimensions.”

Let width = x, then length = x + 7

Area: x(x + 7) = 120

x2+7x=120x^2 + 7x = 120×2+7x=120

x2+7x−120=0x^2 + 7x – 120 = 0x2+7x−120=0

Using the quadratic formula with a=1, b=7, c=-120:

x=−7±49+4802=−7±5292=−7±232x = \frac{-7 \pm \sqrt{49 + 480}}{2} = \frac{-7 \pm \sqrt{529}}{2} = \frac{-7 \pm 23}{2}x=2−7±49+480=2−7±529=2−7±23

x=162=8 or x=−302=−15x = \frac{16}{2} = 8 \text{ or } x = \frac{-30}{2} = -15x=216=8 or x=2−30=−15

Since width can’t be negative: x = 8 m

Length = 8 + 7 = 15 m

Discover More High-Impact Learning Content ➜ Explore expert guides, career resources, and preparation tools to elevate your skills.